Counting Brick by Brick: Cataloging My Collection

/How many Technic friction pins are in your collection? Wouldn’t you like to know? Okay, probably not—but there have got to be some pieces that you’d like to have exact numbers for. So, why not count them?

Well, if you’re looking at a 60,000+ piece collection like I was, you’ll need a better reason than mere curiosity to count out all those pieces. A reason to catalog your pieces might include having a handy way to see exactly what pieces you have available to build with—which would be especially useful if you buy instructions or build MOCs digitally and then physically. But for me, the reason was “needing” to know how much my collection was worth.

So, in early March, I started counting. Two months later, I finished cataloging. And now, two months after that, I’m finally far enough away from the process to talk about it without immediately feeling exhausted. So join me for a walk through my cataloging process—but be warned, it was no walk in the park!

Counting

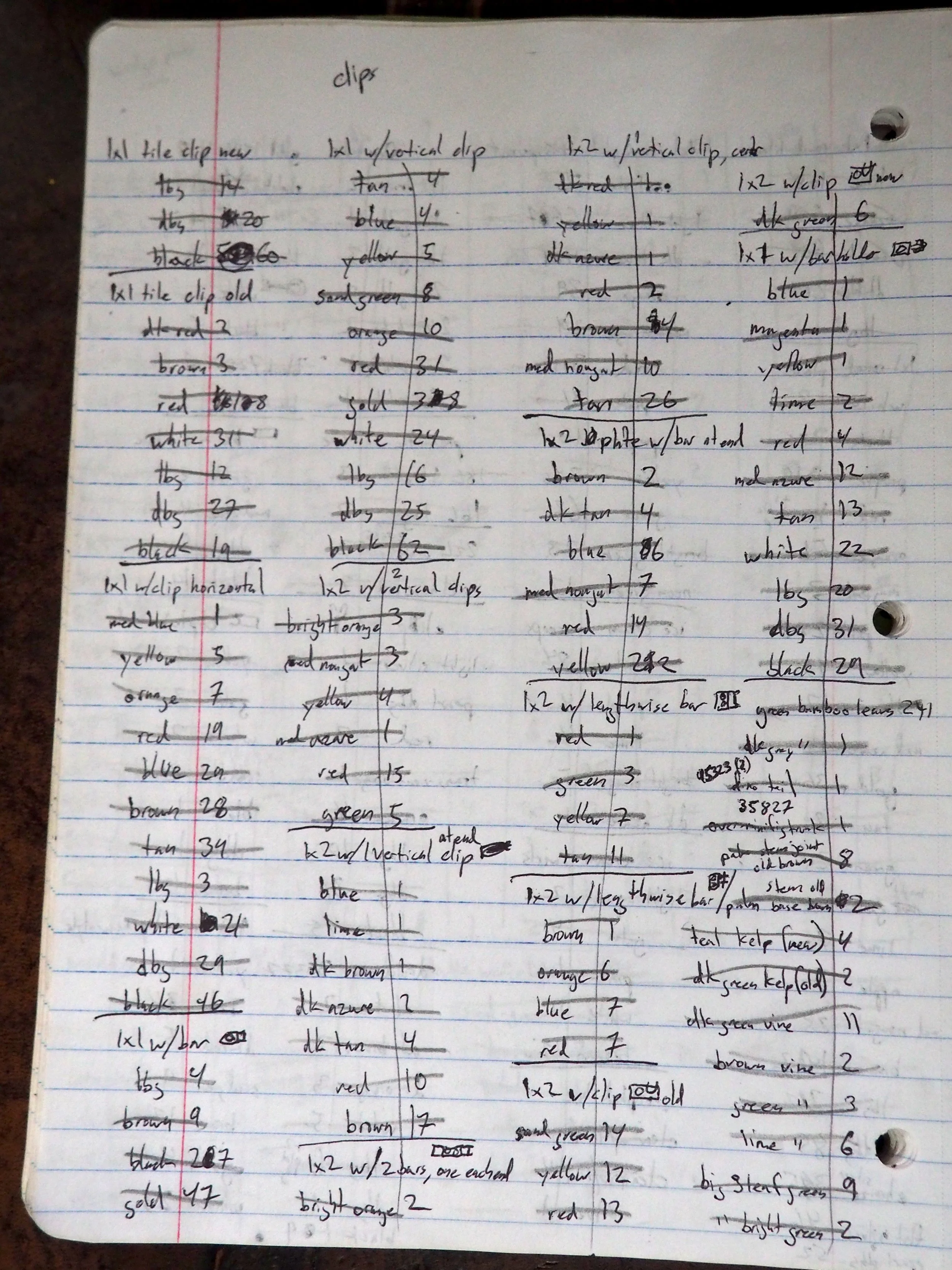

Of course, before you can even get to the counting, you need to do some sorting. Fortunately, I have a well-sorted collection. Still, sometimes there are several varieties of elements, not to mention colors, in the same bin. Here, for instance, I have all these clips and bar bricks in one bin, so I sorted them out by element and then by color. And now it’s time to count!

These clips and bars are all fairly low in quantity. For higher quantities, counting by fives (and for really high quantities, arranging those in rows of fives) is absolutely invaluable. It keeps you from losing track and is actually faster than counting one by one since it’s pretty easy to see five of a part in a single glance without having to actually count them.

Now you could theoretically go straight from the parts on your desk to the catalog, but my computer isn’t too close to my building desk. When I did bring some parts over to my computer to input them that way, I found switching from the mouse/keyboard/screen to the bricks over and over was kind of distracting and less productive than just writing all the parts down and inputting them later. So, I wrote almost all my parts down.

Of course, you can’t write down 60 thousand parts without developing some sort of system. My simplest system was just rows with a element name heading, color on one side, and quantity on the other. This works well for things like clips that are sorted in my collection by element, not color.

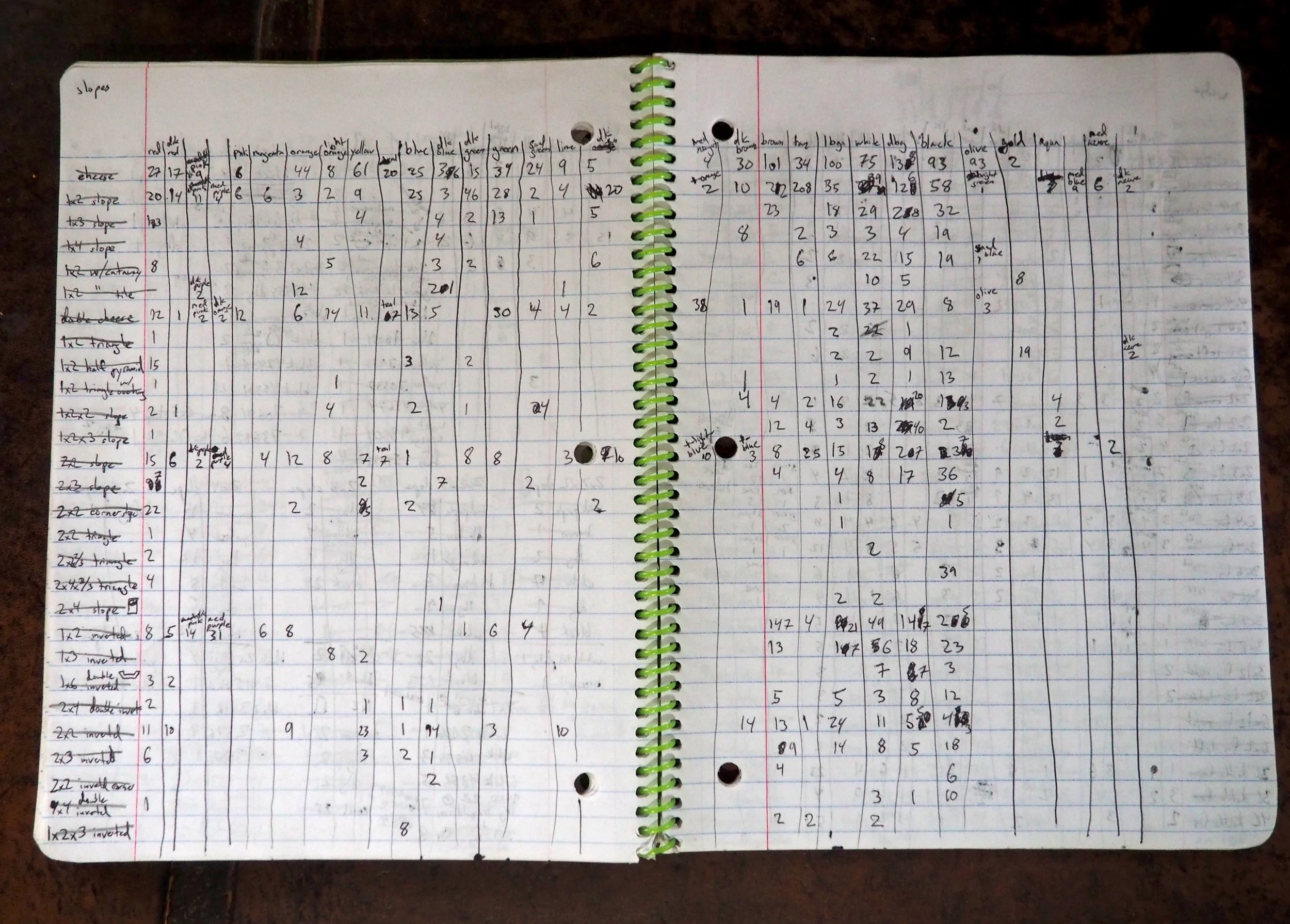

But what about things that are sorted by color, not element? It’s way easier to input a list of parts into Rebrickable if they’re all the same element, then different colors, rather than doing the same color, then different element. So I developed a system that allowed me to count out a bin of one color but a variety of elements (column) and then input it as one element in a variety of colors (row).

Why is everything crossed out, you ask? Well, once I finished inputting a row, I crossed out the element name.

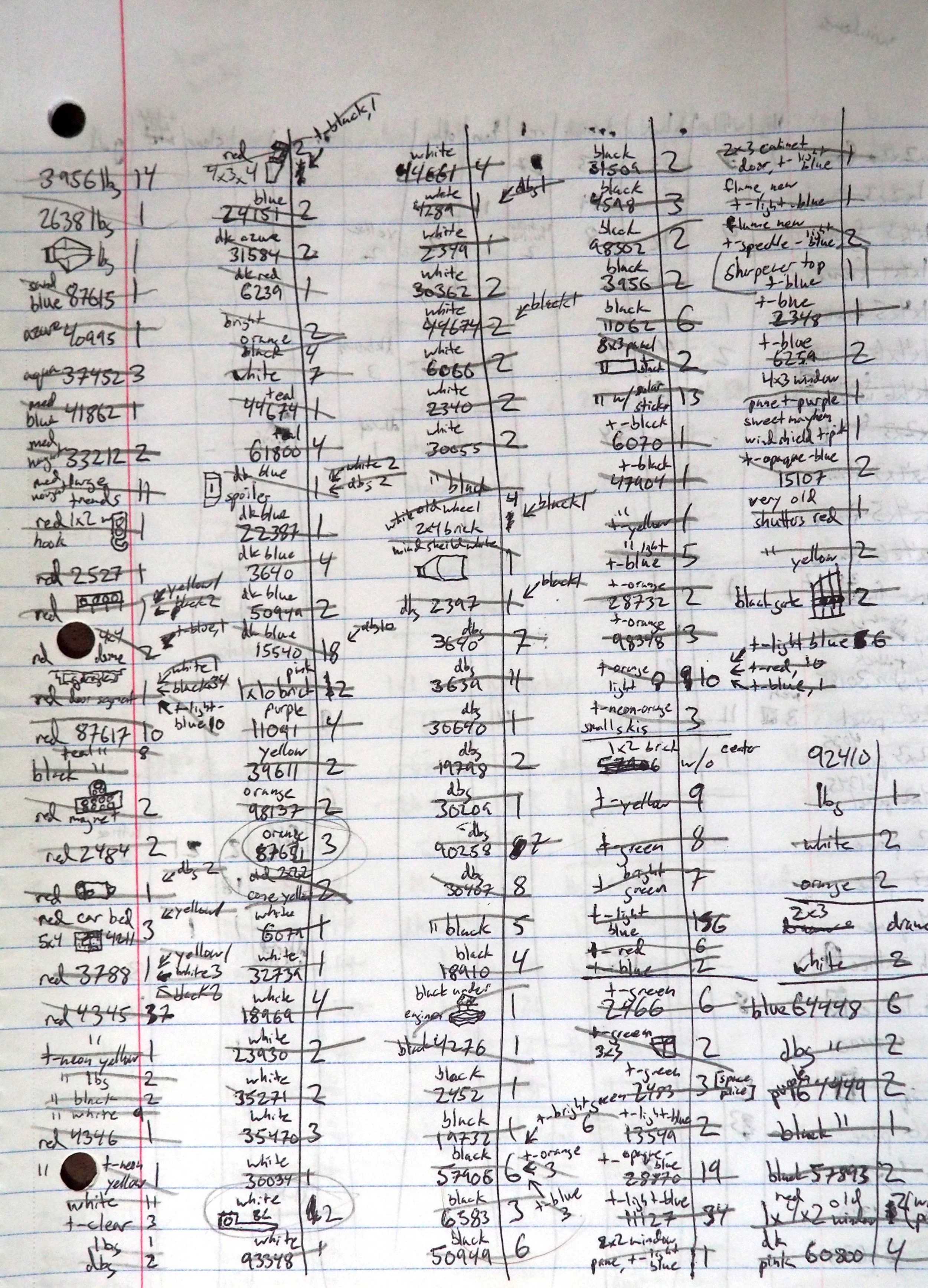

Of course, there are always those elements with mystifying names. I spent plenty of time peering inside bricks trying to decipher the element number. There’s a certain angle that catches the light perfectly…

Please also notice my little drawings of some elements whose element number I couldn’t find. I’m very proud of that windscreen in the middle of the page.

Cataloging

Okay, so we have thirty or forty hand-written (or hand-drawn) pages of LEGO elements. Whew! Almost done, right?

Nope. That was the easy part. Now comes hours of typing out element names (and thinking how much better-named everything would be if you had done the naming), finding colors in a drop-down menu (where on earth is teal and since when did dark turquoise make sense?), and then inputting quantities. Boring!

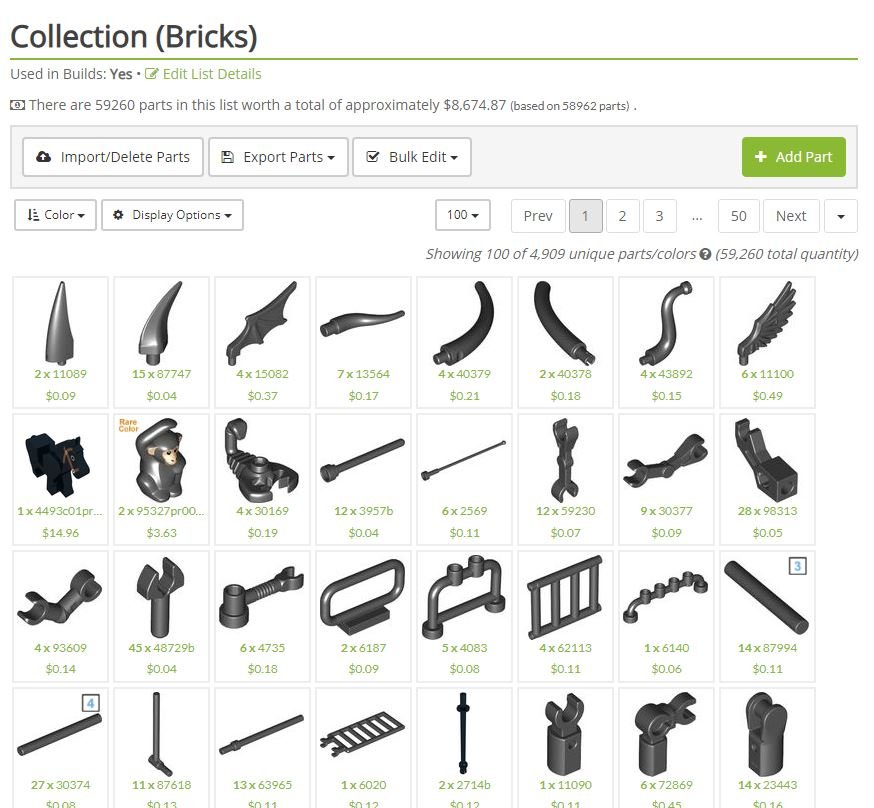

I used Rebrickable for my catalogue. Although it doesn’t use BrickLink names and colors (I don’t think they’re quite the official LEGO names either, but it’s closer), it’s easy to export a list in BrickLink XML. There are other options for cataloging, but Rebrickable was the one I already had an account with so I didn’t feel any need to go further and be worse off.

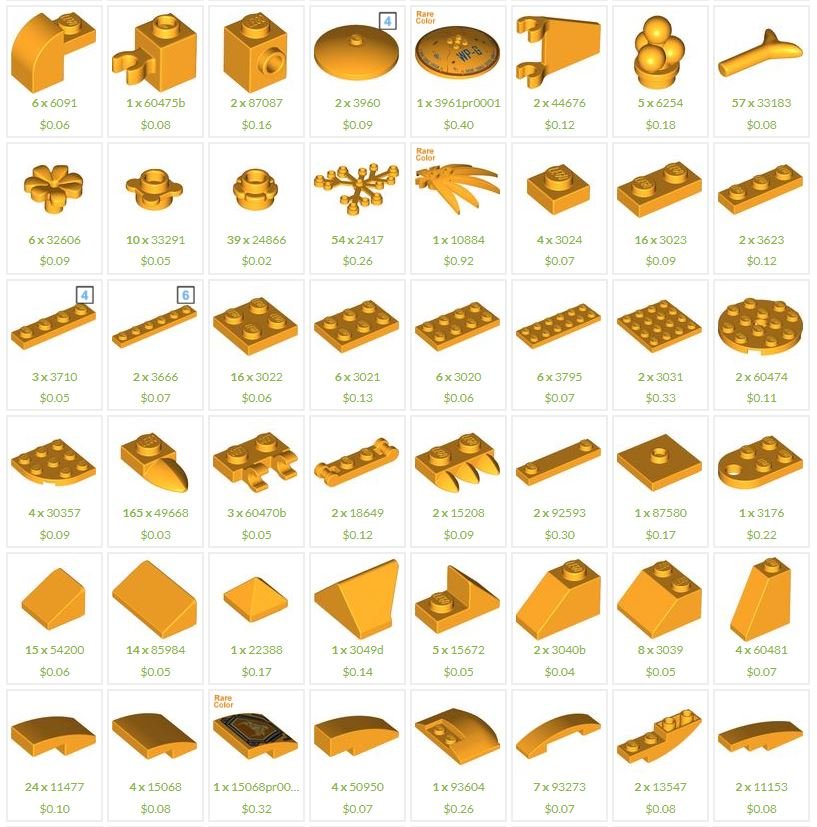

We’ll get to the inputting process in just a minute, but first a couple of notes on Rebrickable “lists;” free accounts are limited to 5,000 parts per list (I maxed out, but there’s no hassle to creating a new list). The prices listed underneath each part are fairly accurate (but occasionally ludicrous) and the handy “rare color” or “color error” messages in the top corners let you know if you potentially made a mistake and called that “bright pink” piece just ordinary sensible “pink.”

It’s very easy to search within your list by color or element or keyword, and you can sort it by price or element or quantity or a couple of other useful things. Anyway, here’s my “dark yellow” collection… which I discovered is actually called bright light orange (who knew!?).

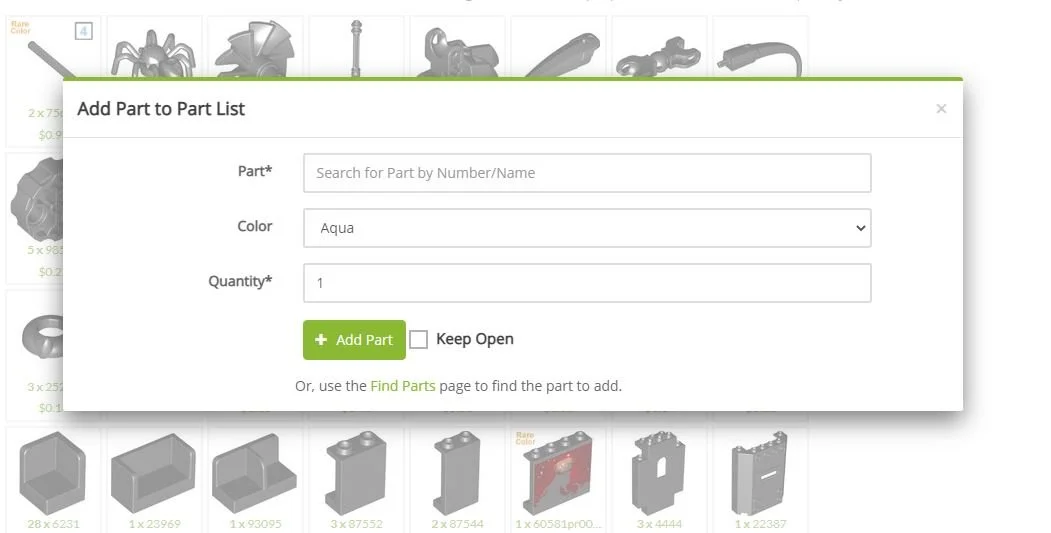

Now for the “adding parts” process. There are a variety of ways to do this; you can import BrickLink XML, LDD, or Stud.io files to name just a few of the importing options. You can even upload your own document with parts, colors, and quantities in rows. But since I don’t have all element numbers memorized, Rebrickable’s “add parts” dialogue was the easiest option for me.

For speed and efficiency, be sure to check the “keep open” box at the bottom. I forgot that several times and had to start at aqua again (which, it turns out, is not the aqua we all know and love… that’s light aqua. Lovely…).

So, here’s the lowdown on the fastest way to power through the adding parts box.

Search for the part. Keep it short; the field only takes twenty characters. (Some elements are too recondite or just too long to show up with shortened titles. Try searching for the category—brick special, or whatever—and if that fails, you can take it to Rebrickable’s catalog.)

Once you’ve found the part, you can place your mouse over the color drop-down menu. If you’re on a laptop like me, this makes it easy to switch colors later on (keeping the element the same). Open the menu, and use the first letter to find the color you want. Repeating a letter takes you further down that letter’s list of colors. So “rr” takes you from red to reddish brown, for instance.

Then hit “tab” and type in the quantity, hit the enter button, and you’re ready to select a new color, input a new quantity, and keep chipping away at that list!

For a while, I double-checked the list after inputting bricks to make sure I’d gotten the quantities right. But that got old.

You can also add parts directly from that part’s page in the catalog or from a page of the catalog listing a bunch of parts. This is handy for those odd parts whose names no one could possibly guess, so you have to scroll through a whole category to find them (or worse yet, go find the set they originally came in). If you have multiple lists, be sure you put your part in the right one!

By the way, I did not catalogue my minifigure collection. When I first started counting, I was intending to, but it didn’t take me long to realize what an immense headache that would be. My bricks are mostly in like new condition so new prices give me a decent idea of what they’re worth—but that would not be the same for my minifigure parts.

Conclusion

Remember my reason for cataloging my collection—”needing” to know how much it was worth? Yeah. After two months of laborious counting and cataloging, you know what? I could totally have just estimated. That was my first reaction, and it’s still my final conclusion. But I did find some pros to the cataloging process, so let me count them out for you:

You get to know your pieces really well.

You get to know what LEGO elements are actually called. (Bar connections are called handles? And the color that I’ve always thought was “lavender” is actually “medium lavender” while “light purple” is the real “lavender?” And “pink?!” don’t get me started on “pink”…)

You have the satisfaction of realizing just how much your collection is worth and feel better about driving your parents’ car while your friends are buying their own.

If you want to sell bricks, you can see exactly what parts you have and what they’re worth.

if you use all or most of a certain part in a MOC that you don’t intend to sort out after, you can replace your previous quantity easily.

Now, in fairness to the pro cataloging side of the story, I left that collection almost immediately and have been building with a second, smaller, uncatalogued collection ever since. So I haven’t really experienced the biggest pros of cataloging just yet:

Quickly looking up exactly how many of a certain part you may have and knowing instantly whether or not a certain technique is viable with your collection.

Comparing quantities of a certain piece and figuring out which color of that piece is best to use as filler.

So much for the pros. Now for the cons:

Counting pieces takes a long time.

Counting pieces is boring.

Cataloging pieces take an even longer time.

Okay, that really doesn’t sound too bad. Thinking about it now, two months later, it wasn’t really too bad. But would I do it again? No. In fact, I’m not even maintaining my current catalog (I brought a lot of parts from my main collection to my second collection, and I just don’t feel like counting them and subtracting them—the catalog has already served its main purpose).

But I will say this: if you dream of cataloging your collection sometime in the future, just stop what you’re doing, get up, and go catalog it RIGHT NOW. Don’t buy ONE SINGLE BRICK MORE before you’ve cataloged it because trust me, by the time you get to the end you won’t want to count one single brick more than you have to!

What’s the largest quantity of pieces you’ve ever counted? Do you dream of having a cataloged collection? Let us know in the comment section below!

Do you want to help BrickNerd continue publishing articles like this one? Become a top patron like Charlie Stephens, Marc & Liz Puleo, Paige Mueller, Rob Klingberg from Brickstuff, John & Joshua Hanlon from Beyond the Brick, Megan Lum, and Andy Price to show your support, get early access, exclusive swag and more.