Tormod Askildsen: One Last Chat with LEGO's AFOL Advocate, Part 2

/In the second part of our interview with Tormod Askildsen, we’ll hear more about how he spent the first half of his career working to get The LEGO Group to realise that they need to pay attention to their ever-growing adult fan base.

Tormod with the Nerd of Note trophy, a distinction only for the few. Tormod is a most worthy recipient

In part one, we left Tormod’s LEGO room just as he was starting to warm up on a topic that’s been close to his heart for many, many years: AFOLs. As we mentioned, the first time the LEGO Group invited adult fans into the company, for consultancy purposes, was before the launch of the second generation of LEGO Mindstorms, the NXT, in 2006. But by then, Tormod had actually been aware of the existence of AFOLs for more than ten years.

The rec.toys.lego Set Review Archive. Image via Brickset

“The first time I came across adults with an interest in LEGO products was as early as around 1995. I got my first work computer around that time, and I spent the entire summer of ’94 or ’95 learning to use it, just by myself. I was all over the Internet! Then, I think that was in late ’95, I searched for “LEGO” on AltaVista, which led me to rec.toys.lego, a group where people talked about sets and made reviews and so on. That was my first encounter with AFOLs.”

Four years later, he became a part of LEGO Direct, which had been set up in 1999. Around this time, Tormod started to segue from working on LEGO Mindstorms into what would arguably become the focus of his time for the next fifteen years.

(If you’re particularly interested in the parts of Tormod’s career that is covered in the next paragraphs, you can find the backstory of the LEGO Ambassador Network (LAN) in our recent article!)

AFOLs Getting Involved

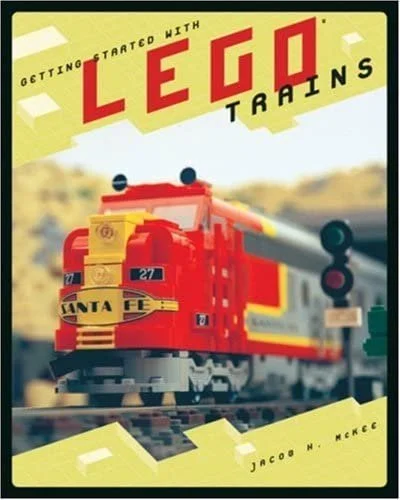

“Getting Started With LEGO Trains” by Jake McKee

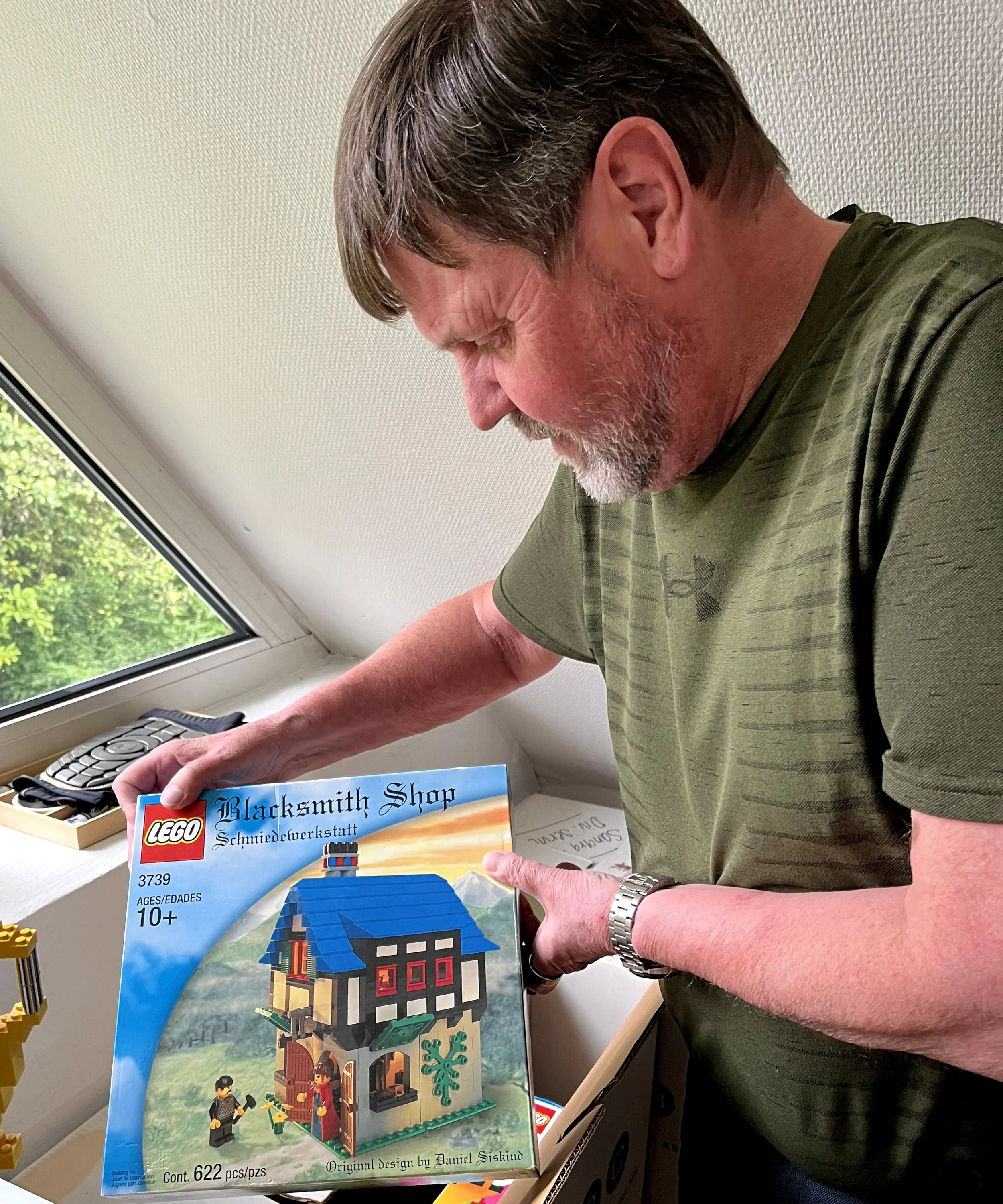

“LEGO Direct was located in New York. They were doing a lot of outreach and collaboration with AFOLs at the time—Jake McKee, who was the community guy over there, did these customised trains you could buy, and we had AFOLs in the office in New York doing mosaics and all kinds of stuff. Via LEGO Direct, the very first user-developed LEGO set came to be: Set #3739 Blacksmith Shop (in the pictures below), created by Daniel Siskind of Brickmania, in 2001. I joined that team, started working with Jake, and brought in Katharina Sutch, an Austrian colleague who worked in the US at the time. Together, the three of us wrote something we called a white paper on “LEGO Enthusiast Communities”, in 2002.”

This document was the first—of many!—attempts at collecting and digesting some information about the LEGO fan community, for use internally in the company, to make their colleagues understand this strange universe that was steadily growing, outside of the LEGO target group.

“We needed to try to get our heads around this. Our white paper was basically about what the fan community was, what we could do, what we thought we should not do, and what they wanted and needed. Plus, why were they even there, and who were they, really? It was very US-centric at the time, even though some communities were also emerging in Europe, with the Brickish Association in the UK, and 1000steine.de in Germany. Oh, Germany…”

Tormod giggles a bit. I can sense there’s a story coming.

Members of 1000steine.de gathered in October, 2000. Image via Ben Beneke on 1000steine.de

Germany: Home of the Brick?

The 1000steine-Land event in 2003. Image via Ben Beneke on 1000steine.de

“Jake spent some time in Germany to talk with fans there. But there was something about the Germans… I think it came down to them not really respecting an American when it came to the LEGO hobby. Essentially, you know, they felt that as Germans they had a special relationship with the LEGO hobby and that Americans, at the time, did not have the same, long tradition for sophisticated LEGO building—so having an American as their LEGO community liaison was almost an insult.”

“I sensed this pretty clearly, and Jake admitted that he had some problems getting close to them. Then my wife, who was working in the legal department, told me about this young German guy who was working with lease agreements for future Brand Stores, but who was also a huge LEGO fan, building things and talking about his favourite LEGO sets all the time. He was located in the area, so I got in touch with him, and I told him I needed a German to work with the German speaking fans.”

The German solution: Jan Beyer, here at the 2005 LEGO Fan WeEkend in Skærbæk. Image via Byggepladen on Brickshelf

His name? Jan Beyer!

“Jan started part-time in 2004, and then eventually became Community Manager. He went straight to the German fans, and they liked him, and he understood them. He was not just this corporate LEGO person—he was German, he was a fan, one of them, really.”

Tormod askildsen and Jan Beyer BrickHeadz, built by themselves at a team building event for the AFOL Engagement Team in 2018. Image via Sara Skahill on the LEGO Ambassador Network

Four Shades of Grey

But even with a proper German fan dealing with the German fans, the LEGO Group were not prepared for what hit them in 2003: The huge colour change drama.

The picture posted by Joe Meno on LUGNET

“That’s the first time that we really felt the wrath of the AFOL community. I remember Joe Meno of BrickJournal posting a picture, noting that something was off with the shades of grey and brown… and oh boy. We had no idea what was coming. Working with AFOLS, we could immediately see that this was not good, because they had these big collections with so many bricks in these colours, and they wanted things to be compatible. But the response from the rest of the company was, “But we tested it!” So we asked who they had tested it with.”

“With moms in Germany, of course...”

“You see, moms loved the colours. They were brighter and cleaner and simply more appealing to them—and they, and their children, were the target group! So I think we had that going for a couple of years, almost, and there was at least one petition to bring the old colours back, made by Ben Beneke in Germany. Eventually everything culminated with none other than new CEO Jørgen Vig Knudstorp responding to the petition, actually writing an open letter where he admitted that we made a mistake by not testing and getting input from AFOLs. That’s pretty unique.”

The wrath of the AFOL community unleashed. Image (slightly edited) via Jeff Eaton on Flickr

It's pretty easy to see that something was needed to explain the AFOL way of thinking to other people inside the company, so an additional project was conceived to help with that.

Teaching the Company about AFOLS—and AFOLs about the Company

The original “AFOLs” comic from 2004

“We came up with a comic called simply “AFOLs”. It was created for us by Jake McKee and illustrated by AFOL Greg Hyland, and it’s absolutely hilarious. It was super important for us to get across what the deal with AFOLs was. We had a huge education job to do, because the vast majority of our colleagues just didn’t get it. They kept talking of a “shadow market” thing, and we never ever actually measured sales outside the 0-14 target group up until a few years ago.”

The AFOL comic eventually found its way to a larger audience through BrickJournal, but the original little leaflet came out in 2004, aimed at LEGO employees. It starts with a foreword from Kjeld: “If this is your first exposure to the adult LEGO community, let me welcome you. You’re about to meet some talented and friendly people who will amaze you every day.”

it’s easy to see that AFOLs were involved in creating the little leaflet that was distributed within the company

Something else was also created in 2004—something very expensive that has ended up on the bucket list of many an AFOL around the world.

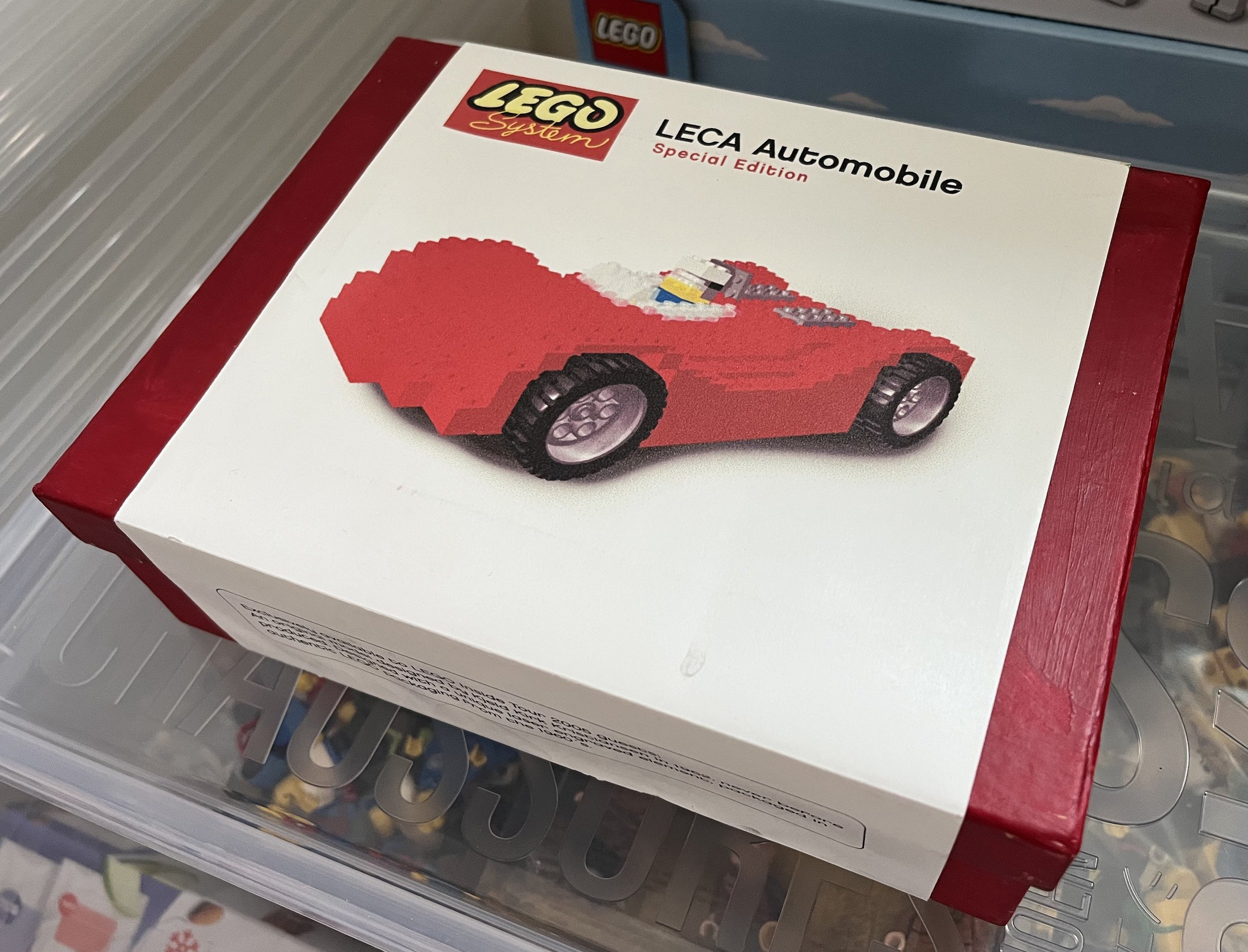

The first Inside Tour set from 2004—an incredibly sought-after (and hand-painted!) box from Tormod’s own LEGO vault

“The LEGO Inside Tour was started by Camilla Torpe. That’s a brilliant concept. I have to tell you something about the very first exclusive Inside Tour set though. The car it depicts is actually a replica of something Kjeld built as a teenager. Kjeld did a lot of “illegal” stuff, cutting and gluing parts for the exhaust pipe, and he was of course painfully aware of that, but at the time, that was also a way for him to tell his dad that “We need parts to be able to build something like this!” The set has a DVD with a message from Kjeld, it has digital building instructions and of course the bricks needed to build the car… but the most amazing thing about it is actually the packaging. Camilla and her daughter bought the cardboard boxes and hand painted all 15 or 20 of them in the basement of the building where we were located at the time.”

There have been fifteen LEGO Inside Tour seasons after that, and almost as many exclusive sets, but I have to say, the first one definitely takes the cake for exclusivity.

(If you want to read more about this year’s Inside Tour, you can read Wayne Tyler’s articles right here on BrickNerd: Part 1, part 2, part 3)

2005: Three Big Things

The following year saw the birth of several innovations that last to this day, two of which were conceived in parallel: The LEGO Certified Professional Program, which has since then grown from four to 22 LCPs, and the LEGO Ambassador Program.

“Representatives from twelve LUGs were involved in the first year. But early on, we encountered one big problem. We basically saw these people as ambassadors for the LEGO brand, that was their purpose to us. They were awesome builders, and we wanted to work closely with them so they then could go out and tell the world how awesome the LEGO brick is. But in some of the dialogues we had with them, things came up that they clearly could not be allowed to talk to outsiders about. We didn’t tell them any big secrets, of course, but the easy way out was to simply put them under a non-disclosure agreement, or NDA.”

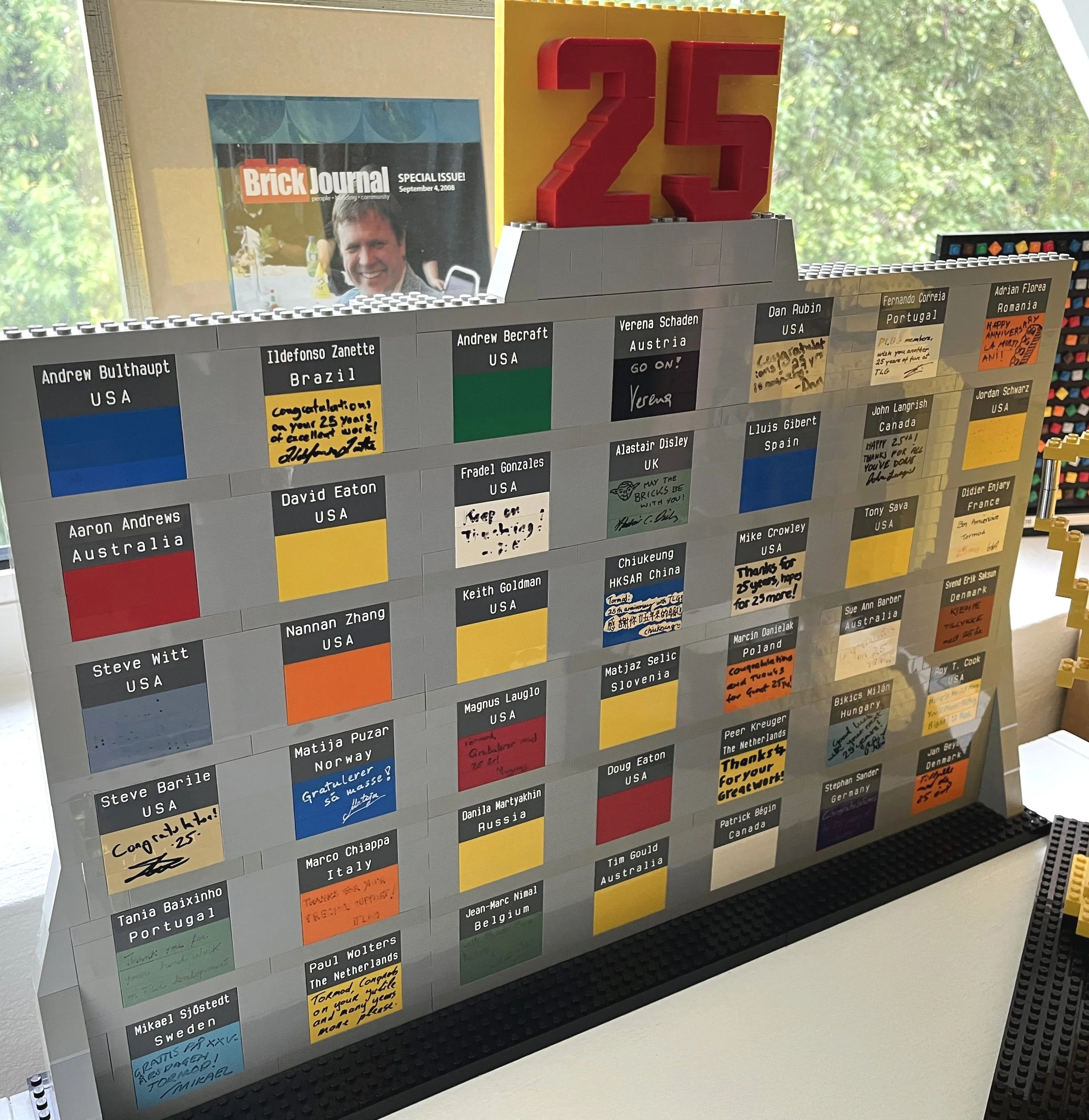

Custom-made wall of greetings from all the LEGO Ambassadors in 2008, for Tormod’s 25th anniversary at the LEGO Group

That was also what the company’s legal department wanted, but that decision backfired completely.

“The consequence was that we took out these people who were all among the leaders in the AFOL community, and after a year or two we realised that they didn’t dare to talk to anyone about anything. They were simply too scared that something would slip!”

The solution was to turn everything around: Instead of being ambassadors for the LEGO Group or the brand, the selected people became ambassadors for their respective user communities. And today, NDAs are never used with the LEGO Ambassador Network (LAN), also meaning that LAN Ambassadors cannot participate in projects where sharing of confidential information—and signing of NDAs—are needed.

Danish AFOL Peter Vingborg setting up for the 2005 LEGO Fan Weekend in Skærbæk. Image via Carsten Straaberg on Brickshelf

The final big new innovation of 2005 was the LEGO Fan Weekend. It was run as a collaboration between the LEGO Group and a group of fans for ten years, from 2005 to 2014, until the company decided to pull out. Luckily, it arose from the ashes the very next year as the Skærbæk Fan Weekend.

“I have a fan-designed, engraved 1x8 brick here somewhere, saying “Save Skærbæk”. A lot of AFOLs were angry with me when we withdrew, and I mean really, really angry. But the intention of the event was basically for Jan Beyer to find out what kind of a commitment it would be, it was an investigation into what it takes to host an AFOL event. It was never meant to run for that long. After six or seven years, I told Jan that it was time to let it go, and then it lasted for ten. Then, of course, the guys who run it now eventually stepped up, Stephan Sander, Thomas Wesselski, Caspar Bennedsen, Lluís Gibert… they were all so angry, but I think they have seen that it was really for the best. The LEGO Group has continued to support the event, but it was after we pulled out as organisers that it really started to grow!”

At the closing speech of the 2022 Skærbæk Fan Weekend. Note that there isn’t a single member of the public in this picture, it is all LEGO fans in attendance—1,101 of them. Image via OrangeTeamLUG on Flickr

The reason Tormod wanted Jan Beyer, and the LEGO Group in general, to find out what it was like to get an event like that up and running, was that several such events had popped up in several different countries in the years leading up to that. A lot of people were investing money and time in AFOL events.

The BrickFest website back in 2000, inviting AFOLs to join the inaugural event

“I mentioned MindFest earlier, the event organised by MIT Media Lab in 1999, where we first met up with the Mindstorms “hackers”. One of the participants at MindFest was a girl named Christina Hitchcock. She was so inspired by what she saw there that she went back home and started planning, The year after, in 2000, she organised the first BrickFest—at George Mason University in Washington, D.C.—and to me, that is the first time a real AFOL event came together. Now, I try to say that at events in the US, and then people say, “No! Surely it was this group over there, they did something earlier, in...” –well, maybe. But to me, BrickFest 2000 was the first significant AFOL event, and all the other events grew from there. The first fan event that I physically attended was an event called BricksWest, that only happened once or twice, in 2003, but I’ve lost count of all the ones I’ve been to since. My collection of brick badges probably tells that story better than I can.”

A small taste of Tormod’s giant brick badge collection, with him pointing at the very first one, BricksWest 2003

The Huge Crisis

A serious CEO Kjeld Kirk Kristiansen in the LEGO Group’s annual report from the crisis year of 2003

When it comes to the chronology of Tormod’s career though, we’re getting a bit ahead of ourselves. Because in order to even get to the events of 2005, he and the rest of the company had to get through one of, if not the worst crisis that it has experienced.

“In the early 2000s, I felt that we had hired so many people who did things that I was extremely puzzled about. Now, I’ve always been on the fringes of the LEGO Group, in LEGO Education, First LEGO League, working with AFOLs, LEGO Mindstorms, LEGO Factory… all things outside the core operations of the company, and I didn’t want to get closer to the core, because I wanted the freedom to pursue things that I personally found meaningful and that gave me energy. That meant I didn’t feel the full blow of the crisis like many of my colleagues did, who were at the very heart of the business, so to speak. But I was very puzzled by a lot of this. LEGO Mindstorms was scrapped, and another technology project starting up with a huge level of ambition. The DUPLO name was scrapped, replaced by something called LEGO Explore. And we launched Galidor… there were of course lots of good, academic reasons for these decisions, but the things that happened there really hurt. For someone who had been around for 20 years at the time, it didn’t feel right at all. Many colleagues were wondering what was going on.”

In January 2004, Kjeld Kirk Kristiansen essentially replaced himself with Jørgen Vig Knudstorp as company CEO

“This was, of course, when Kjeld decided to put Jørgen Vig Knudstorp in charge, he became CEO in 2004. Jørgen came from McKinsey a few years earlier and had developed a very good understanding of the company, and he started a project and a new strategy called Shared Vision.”

A lot of different workstreams were started in 2005, and Tormod was driving two of them.

“One of the key decisions I was involved with was defining the LEGO brand as a premium brand. Research showed that there was a market for a toy manufacturer to go premium, and this has influenced everything we have done over the many years that have passed. You can see it on the sets and the quality—of course, AFOLs will always argue about colour consistency and stuff like that, but it also applies to many other things, like the Consumer Service setup, to make the LEGO brand a premium brand.”

What the LEGO Group likes to tell us that their customer service offices look like. Image via the LEGO Group

Speaking of arguing AFOLs—new strategies and relentless work to make the company understand the AFOL community better has not improved everything.

Another Fallout—and Introducing the New CEO to the Fans

A lone protester at Brick Blast 2006. Image via NELUG.ORG

“The next fallout we had with the fans was the decision to remove the metal from the train tracks, and switching to battery power. For AFOLs, and especially those who organise these huge displays at events, that was understandably a nightmare. I have another engraved 1x8 brick saying “Save 9V trains”. But we got through it, and we had a very close collaboration with a lot of people around this, both AFOLs and LEGO colleagues. We also ended up discussing train track radii. The AFOLs wanted several different ones, and we told them that was madness from a business perspective, because there is simply no market for it on this scale. But then we gathered a group of train people who actually came up with the compromise that lived for a while: the flex track, a small piece of flexible track to flex the curve. That was a co-creation project with train fans, an AFOL consumer driven project.”

The flex track, released in sets from 2009 to 2018, was a direct result of communication with train fans

Eventually, Tormod became an even more integral part of Shared Vision, Jørgen Vig Knudstorp’s strategy.

“Jørgen brought me in, I think very much because of Kjeld. As I’ve mentioned, Kjeld was fascinated by AFOLs, and he talked to Jørgen, who then came to me and said that he wanted to get to know these people better, at least some representatives from the fan community. So Jake and I took him, his wife and kids, and Kjeld, to BrickFest in 2005.”

Jørgen Vig Knudstorp speaking to fans at BrickFest 2005. Image via Philip J. Moyer on Brickshelf

Kjeld, Jørgen and Tormod at BrickWorld Chicago, 2009. Image via Bill Ward on Flickr

And the new CEO really put in the legwork.

“Jørgen spent the entire weekend on meetings with different groups—the castle people, the train people, the space people, very segregated at the time. I think what Kjeld had said to Jørgen was something along the lines of this: “If anyone on the planet knows what the essence of LEGO play really is, it is our adult fans.” So he had really deep conversations with them, he really got an understanding of this, and for as long as he was CEO, AFOLs were super important to him. I don’t know how many events he has travelled to, many times alone, or together with Kjeld. So many dialogues. And AFOLs kept emailing him, too, I don’t know how much, but from time to time he kept forwarding emails to me, and asking what could be done with this and that issue that some fan had brought up.”

From then on, AFOLs really started coming into their own—just like the new CEO. But we’ll save the story of the arrival of modern AFOL-dom and Tormod’s integral impact on the community for the final part of our conversation [now available].

Have you bumped into Tormod at an event—or maybe even Kjeld or Jørgen? Do you have experience with the German AFOL community, or do you still shiver at the thought of the 2003 colour change? Let us know in the comments!

Do you want to help BrickNerd continue publishing articles like this one? Become a top patron like Charlie Stephens, Marc & Liz Puleo, Paige Mueller, Rob Klingberg from Brickstuff, John & Joshua Hanlon from Beyond the Brick, Megan Lum, Andy Price, and John A. to show your support, get early access, exclusive swag and more.